Titratable Acidity

(Pending review and updates from Mike Castagno)

Titratable Acidity (abbreviated as TA) is an approximation of the Total Acidity of a solution, and has long been used in the production of wine. It is usually expressed in units of grams per liter (g/L), although other formats are also used [1]. Titratable Acidity is often mistakenly confused with Total Acidity, but they are not the same thing [2]. While Total Acidity is a more accurate measurement of the total acid content of a solution, Titratable Acidity is used because it is easier to measure. Although titratable acidity does not measure all acids, TA is generally considered a better way to measure perceivable acidity in sour beer and wine than pH [3].

Contents

TA versus pH

Many sour beer producers use pH to help determine how "sour" their beer is in relation to a set goal, previous batches, or commercial examples. However, often times TA is a more accurate measurement of how acidic a beer will be perceived on the palate.

pH

In chemistry, pH is the negative log of the activity of the hydrogen ion (H+) in an aqueous solution. Solutions with a pH less than 7 are said to be acidic and solutions with a pH greater than 7 are basic or alkaline. Pure water has a pH of 7.

The pH scale is traceable to a set of standard solutions whose pH is established by international agreement [4]. Primary pH standard values are determined using a concentration cell with transference, by measuring the potential difference between a hydrogen electrode and a standard electrode such as the silver chloride electrode. Measurement of pH for aqueous solutions can be done with a glass electrode and a pH meter, or using indicators.

pH measurements are important in medicine, biology, chemistry, agriculture, forestry, food science, environmental science, oceanography, civil engineering, chemical engineering, nutrition, water treatment & water purification, and many other applications [4].

pH is best tested in sour beers using a pH Meter and is most useful for biological parameters. Microbial growth, vitality, and death are evaluated based on pH rather than TA. This means pH should be used when testing sanitizer, Wort Souring, starter cultures, etc.

TA

Titration is an attempt to quantify an unknown substance with a known one. Titratable acidity asks how much of a given base (in our case sodium hydroxide, NaOH) neutralizes the acid(s) (lactic, phosphoric, etc.) in a volume of liquid. The units of TA can be quoted in g/L, or in other words, so many grams (of a specific acid) in so much substrate (beer) brings the pH of that substrate to a predetermined pH (for instance, a pH of 7 or 8.2).

Titratable acidity does not target a specific acid in the liquid you are measuring. Beer is composed of lactic acid, but also phosphoric acid, acetic acid, etc. While the latter are in minute quantities, they still affect the end result. For our purposes (and convention), we assume 100% lactic acid in the sample for our titration.

Why care about titratable acidity? pH quantifies the number of hydrogen ions (or hydrogen ion equivalents) in liquid. Your palate does not measure pH directly. Your palate interprets a multi-variable substrate called beer. Titratable acidity attempts to put another quantifiable handle on your beer akin to pH; the measurement better captures how “acidic” the beer may taste to you. Again, there are other acids than lactic in the beer, leading to differences in flavor between beers of the same TA.

Titratable acidity can be expressed in terms of different acids. In wine, TA is generally expressed in terms of tartaric acid (molecular weight of 150.09). In sour beer, TA is expressed in terms of lactic acid (molecular weight 90.08). To express TA in terms of a specific acid, the molecular weight of the specified acid is used in the TA calculation. In the example below, we express the TA value in terms of lactic acid. See appendix 1 in this paper on how to convert the titratable acidity value for different acids. Note that this is NOT a measurement of how much lactic acid or tartaric acid there is, it is an expression of measurement like how feet and meters are two different expressions of measurement for the same thing (distance). For example, a TA of 3.0 measured in units of tartaric acid is equal to a TA 3.6009 measured in units of lactic acid. Therefore, an argument can be made that TA measurements should always be specified as to which acid was used in the calculation.

Example

"I agree that maths are hard." - Lance Shaner.

What you will need:

- A reliable and calibrated pH Meter.

- Sample of beer to be measured. Must be fully degassed if it has any carbonation (pour through a coffee filter, or shake and ventilate to decarbonate).

- Sodium Hydroxide, NaOH. Available in liquid or powder form. Be sure to note its molarity (M), units of mol/L. For more info on mol, see here.

Safety caution: always wear safety glasses and gloves when handling NaOH in any concentration. NaOH can cause severe burns. In concentrations higher than 0.1, NaOH can corrode through clothing. See Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety on Sodium Hydroxide.

- Nitrile or latex gloves. NaOH is a strong base, it will hurt you if you get any on your skin.

- Pipettes and glassware, with precision down to 0.1 mL. Alternatively, you can use a precision scale to dose the base into the beer, if you know the density of both liquids (preferred method).

We need a precise volume of the beer. In this case, we have 15 mL. We also need NaOH in liquid form. Typically, it is sold in 0.1M form. Now, the trickiest part of this is adding precise amounts of NaOH (say, 0.1-0.5 mL at time), to your 15 mL of beer. Every time you add NaOH, you must vigorously stir the sample so it is well-mixed. Then you can measure its pH. You continue this until you reach the desired pH baseline of 8.2.

- Note: The baseline value of 8.2 pH is somewhat arbitrary, but it is the US and Australian industry standard. A pH of 7 is a neutral pH and the pH of water, whereas ~8.2 is near the equivalence point for a lactic acid/sodium hydroxide reaction. A pH of 8.2 is also where a titration dye, phenolphthalein, changes color. A well-calibrated pH meter is easier to use than dye, not to mention its superior accuracy and precision, if used correctly (well-calibrated, probe well-maintained, etc.). A pH of 7 is the European industry standard for measuring TA in wine [5].

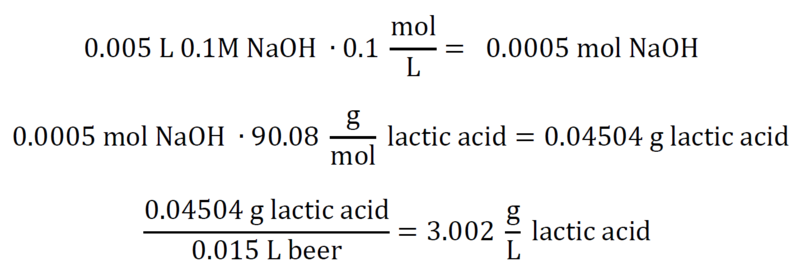

At or around a pH of 8.2, we have reached our equivalence point for a titration of pure NaOH and pure lactic acid. We need to convert the moles of NaOH we added into moles of lactic acid, and then divide the equivalent grams of lactic acid by the original volume of beer. That gets us g/L, and our titratable acidity. For a numerical example, assume 15mL beer, 5mL 0.1M NaOH:

The Eccentric Beekeeper TA Spreadsheet calculates TA as well as blends of beers with different TA values. It also includes a correction for beer final gravity. The idea is that the more residual sugar there is the less effect the acid will have on your perception. This is likely not that straightforward since you can have varying levels of sweetness at the same given FG [6].

In summary, the measurement of titratable acidity is a technique to quantify the total acid level of a beer. A major assumption was made: all the acid in the liquid was lactic acid. Two beers could have the same TA measurement, but have differing levels of palatable acidity, due to the acid makeup of the beer.

Videos

Titration of a weak acid with a strong base by Kahn Acadmey part 1:

Measuring Titratable Acidity in Wine (use the calculation above instead of the calculation in the video to express the value in terms of lactic acid):

Limitations of TA

Although a better representation of perceived acidity than pH, titratable acidity might have some limitations on accurately measuring perceived acidity in beer. See this MTF discussion for details.

See Also

Additional Articles on MTF Wiki

External Resources

- Wort and Beer Titration by Kai Troester.

- More information on this procedure is available from the American Society of Brewing Chemists, who publish a similar set of procedures under the name "Total Acidity with Potentiometer".

- Jim Crooks of Firestone Walker presentation about blending sour beers using TA.

- Dave Janssen's discussion of Kara Taylor's CBC talk.

- pH Readings of Commercial Beers, Embrace the Funk Blog, Brandon Jones.

- Amazon source for NaOH.

- MTF discussion regarding Kara Taylor's BA presentation that shows TA for multiple beers, and suggestion for using "Sour Units" as a measurement for beer.

- MTF tips on what type of NaOH to buy (liquid over dry), and how to handle it safely.

- MTF tips on safety and methods of measuring TA from a research technician.

- "Savoring Acidity: The Quest to Explain Sourness in Beer", by Brian Yaeger in BeerAdvocate magazine.

- "A Guide to Blending Sour Beer With Fruit" by Matt Miller; includes ABV and TA calculators for fruit additions.

Authorship

Originally written by James Howat with major updates by Andy Carter, and with input from Dan Pixley and organic chemist Mike Castagno.

References

- ↑ Wine From the Outside - Easy Wine Chemistry For the Casual Chemist. Monitoring Acids and pH in Winemaking. Mike Miller.

- ↑ The relationship between total acidity, titratable acidity and pH in wine. Roger Boulton. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 31(1): 76-80. 1980.

- ↑ How Sour is Your Sour Beer?. OCBeerBlog on Firestone Walker's demonstration of the uses of TA measurements. April 13, 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bates, Roger G. Determination of pH: theory and practice. Wiley, 1973.

- ↑ "TN14 - Interconversion of acidity units" Industry Development and Support. Australian Wine Research Institute. Retrieved 09/15/2016.

- ↑ Conversation with Dave Janssen on MTF. 6/23/2015.